October 4th, 2020

My son Micah and I left Petersburg at 3:00 PM, headed south on Alaska Airlines flight #64 to Wrangell, Ketchikan and finally Seattle, Washington, where we would stay the night before catching our next flight to San Antonio, Texas. This trip was the much anticipated beginning of a mission I gave myself that few others would understand. I’m not entirely sure I understand it myself. I can remember being interested in the Vietnam War when I was very young. Like other kids growing up in the late 80s and early 90s, I learned about America’s wars in school, and World War II was the focal point of that learning. Vietnam was covered, but not in any in-depth way. My wonderful history teacher, Mrs. Mitchell, did give time for a few Vietnam Veterans to come into her high school history class and speak to us about Vietnam. When other students asked insensitive questions such as “How many men did you kill?” and tried to startle them by pushing their books onto the floor, I sat puzzled and inwardly furious with the juvenile actions of my classmates. As I grew older, my father and older brothers’ choices of reading material gave me ample opportunities to sneak the latest Vietnam biography or novel that they had picked up from the bookstore. The stories fascinated me. Vietnam seemed so different from the island hopping, airborne operations and armored thrusts that characterized World War II.

When I joined the Army after graduation from high school in 1997, my attention shifted towards my own military service. During the next fifteen years, nine of them as an active duty soldier, and the remainder split between a few years working for an oil services company and the rest as an employee of the US Forest Service, I gradually regained my interest in the Vietnam War. This was mostly due to my wife Garnett’s family connection to the war. Her father’s younger brother Donald, a 21-year old conscientious objector and combat medic, had been killed in a friendly fire incident south of Dak To on May 8, 1968. In 2016, while preparing for a 3-month temporary job in Washington DC, I began using the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund website as a source of casual research. Their Wall of Faces remembrance pages of each casualty gave a picture and brief biographical details about each of the over 58,000 men and women who died during the conflict.

I began working with a man named Bill Killian, a high school history teacher in California. I had first noticed his writings on the Wall Of Faces website. He wrote short, fairly simple narratives that gave a glimpse into the circumstances of each individual’s death. I was impressed, so I reached out to him to offer my assistance. After I sent him a few samples of my writing, he agreed to accept my help. Over the next few years, I wrote around 100 narratives for men who had died in Vietnam in the early 1960’s.

At some point, my focus narrowed on the 3-12 Infantry, a light infantry battalion in the 4th Infantry Division that served in Vietnam from September 1966 until December 1970. This was my wife’s uncle’s unit. He had been assigned to Headquarters Company and was attached as a platoon medic in Delta Company when he and two other men were killed in a friendly fire incident on May 8, 1968.

Early on in my research I had stumbled upon the coffeltdatabase.org. Created by a Korean War veteran named Richard Coffelt, it is an online repository of information on over 55,000 of the Americans who had fallen in Vietnam. I visited the page for Corporal Donald Sperl, Garnett’s uncle. There, near the bottom of the page, was a curious link. ‘Display all associated casualty records’. I clicked on it. Three names appeared…CPL Donald Sperl, SGT Albert O’Bannon Jr. and PFC Fred Whiles Jr. All three men had been killed in action in the same friendly fire incident.

My mind raced…Where were their families? Did they know that their loved one had not been alone when he died? Did they wonder? I did a bit of online sleuthing, and discovered the hometowns, parents’ names and addresses and a few other tidbits of information about the two other men.

SGT O’Bannon, a black Seventh Day Adventist had been a conscientious objector and medic like Donald. He grew up in Redlands, California. I found a brief reference to his parents in a snippet from an online text about the Seventh Day Adventist church, but no leads on their whereabouts.

About PFC Whiles, a 19-year-old boy from Tulsa, Oklahoma, I discovered even less information available online. He had only been in Vietnam for a couple of weeks when he was killed, so it was likely that the men who served with him in Delta Company barely got to know him. With not much to go on for these two men, my thoughts turned elsewhere.

What was the battalion doing in Kontum Province? Why was Delta Company on that ridge near Dak To in May of 1968? Where were the other companies of the battalion? HHC, Alpha, Bravo and Charlie? Were they nearby? I began looking at lists of the casualties from the 12th Infantry Regiment. Weeding out records for men from the 1st, 2nd, 4th, and 5th battalions, I started noticing dates with heavy casualties from the 3rd Battalion. This piqued my curiosity even more.

May 30, 1968. May 22, 1967. March 9, 1967. August 14, 1968. November 17, 1967. March 11, 1969……I needed to know more.

Over the next few years, I dug, and I dug. I started reaching out via email to men who had left remembrances of their buddies who had died while serving in the 3rd Battalion, 12th Infantry Regiment.

I started to understand that each of these men who died in Vietnam were so much more than just a name on black granite in Washington DC. These were friends, and sons, and fathers, and brothers. They had left America with so much promise ahead of them, only to be claimed by the relentless meat grinder that was the Vietnam War. They deserved to be remembered. Not as a group, as a mass of names listed alphabetically or chronologically, but as the individuals that they were.

In 2019, I submitted a request for a unit extract of the 3rd Battalion, 12th Infantry from the coffeltdatabase.org. I wanted to be able to see the list of names in an MS Excel document. I wanted to filter, and compare, and not be bound to the static online record the coffeltdatabase.org provided. I received it and was overjoyed at what it provided. A structured breakdown of each of the 267 men from the battalion who fell in Vietnam. Name, birthdate, service number, unit of assignment, MOS, date of casualty, and one of the most intriguing items to me, the location of their final resting place. Cemeteries spread across America, most of them near the soldier’s hometowns.

I took the spreadsheet and started plotting the locations of each cemetery on a custom Google Map. Soon, a new version of America was visible to me. Places like Long Island, New York, Kerrville, Texas, Liberal, Kansas and Tampa, Florida had new meaning. Each one represented the location of a cemetery that held the remains of a man from Uncle Donald’s battalion, the 3-12 Infantry. Most had never met Donald, but that wasn’t the point. If in combat the men in your fire team and squad and platoon are your brothers, then the men in your company are first cousins, and the men in your battalion distant kin, but family, nonetheless. They all wore the same patch, the ivy leaves of the 4th Infantry Division, and more importantly, they all wore the same unit insignia on their dress uniforms, the yellow and blue heraldry of the 12th Infantry Regiment. Most intimately of all, they all lived the motto of their battalion, “Braves Always First.”

I wanted to know each one of the 267 men, and so I began with Donald’s story. I called and spoke to his platoon leader Phil Lawler, and with other men who had served with him, including Mike Pineda, from Mesquite, Texas. Mike remembered Donald fondly and described him eloquently, “Don didn’t believe in killing, yet he served his country because he knew men would try to kill each other and would need to be tended to when wounded. While we carried weapons of destruction, he carried tools of healing (along with a shovel to help us dig fox holes with).” (http://thewall-usa.com/guest.asp?recid=49166)

I visited Donald’s gravesite in Juneau, Alaska on the 50th anniversary of his death in Vietnam. It is located in the Evergreen Cemetery near the heart of downtown Juneau, and just a stone’s throw from Juneau-Douglas High School, where he graduated in 1965. Formally established in 1891, the Evergreen Cemetery holds the remains of some of Alaska’s earliest pioneers and explorers.

Donald’s grave is centrally located in the American Legion section of the cemetery, beneath the shadow of the flagpole that stands proudly amid more than 6000 graves. His parents Walter & Clara Sperl are buried there with him now. A flat gray marker, displaying all three of their names has replaced the original military marker that had been placed by Walt & Clara in 1968. The thickly forested slopes of Mt. Juneau thrust upward just a few hundred yards from Donald’s grave. These were the details I wanted to know about the other men. Who were their parents? Where were they buried? What did the cemetery feel like? Was the grave well-kept or had it been left abandoned and in disrepair?

In 2019, my work brought me to Albuquerque, New Mexico. A quick scan of my gravesite map showed one within driving distance. CPL Willie Danien Martinez from Santa Fe is buried at the Santa Fe National Cemetery. One afternoon, after leaving work a little early, I made the one-hour drive, arriving at the cemetery just as the visitor center was closing. I made my way to Willie’s grave, and sat in the late New Mexico sun, reflecting on what I knew about this man. Willie was the oldest of four brothers and had dropped out of Santa Fe High School after his junior year to enlist in the Army. He was a natural soldier but could not escape the maelstrom that was Alpha Company’s participation in LZ Cider. On March 27th, 1969, he and seven other A Co men were caught in a series of vicious ambushes outside the LZ, and before the battle was over, an additional eight men would lose their lives trying to recover the bodies of their fallen comrades.

I wrote my story of Willie without ever having contacted any of the men that served with him, or family of his that were left behind. Although I was satisfied with the narrative I had written, it lacked the personal connection that would be gained through interviews and personal visits with those that knew Willie. I resolved to do more as my travels brought me to the gravesites of the other men in the battalion.

So that brings me to Texas, and October of 2020. COVID-19 and its assorted effects on life as we know it in America had robbed me of several opportunities to find more information about the 3-12 Infantry. But Texas is open, and so my son and I were on our way. Before leaving Alaska, I spent some time looking at my gravesite map and designed an ambitious circular route that would bring us from San Antonio, down to Corpus Christi, up to Houston and then Mesquite, and back down to San Antonio through Austin. In between those major cities would be visits to six other towns. All but one of our stops held the gravesite of a 3-12 Infantry veteran who had died in Vietnam.

In the months leading up to this trip, I had spent quite a bit of time laying the groundwork. I knew that locating the actual headstone in some of these cemeteries might be challenging if I went in cold. I emailed and called relatives, cemeteries and veteran’s organizations. I used the Find A Grave website, other online resources and personal contact with individuals who had previously visited the gravesites to try and pinpoint plot locations.

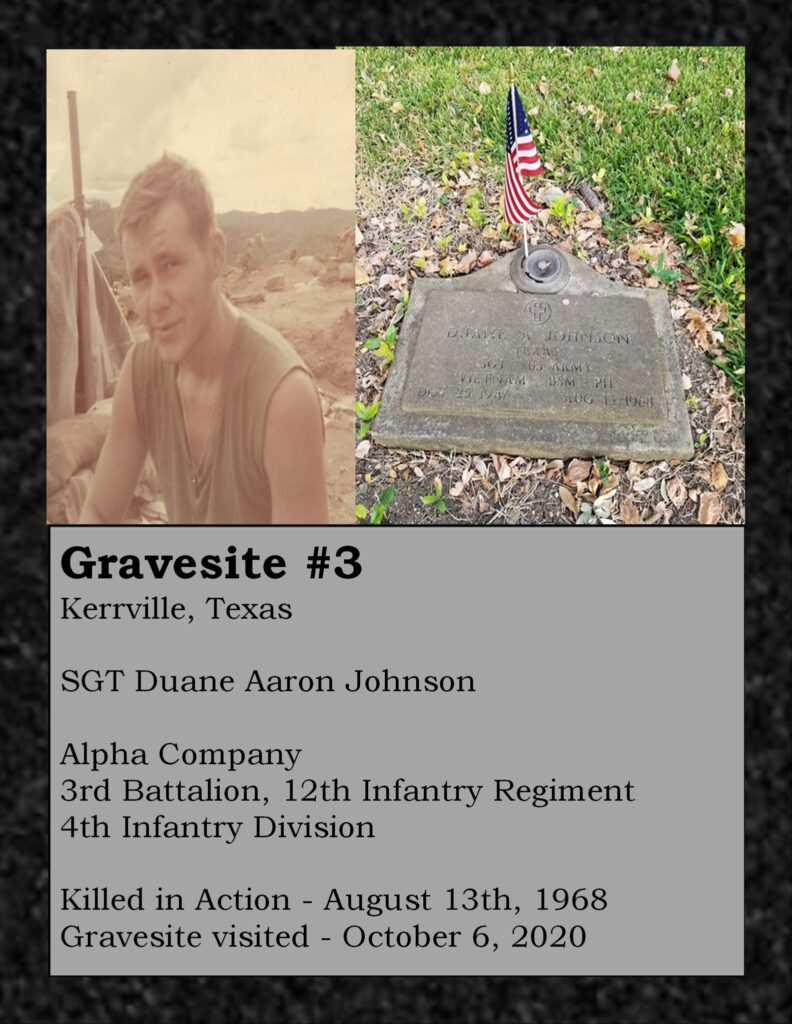

First Stop – Garden of Memories Cemetery, Kerrville, Texas – SGT Duane Johnson, Alpha Company, 3rd Battalion, 12th Infantry Regiment. Killed in Action on August 13, 1968.

Roughly 24 hours after leaving home, on October 5th, 2020 at around 3:00 PM Central Time, my son Micah and I landed at San Antonio International Airport. We secured our rental car and began our journey through Texas. We didn’t linger in the city, but instead drove up I-10N towards Kerrville, Texas. Dodging a bit of construction on the way out, we soon found ourselves enjoying the rolling landscape of Texas hill country. Although anxious to get the ball rolling on the gravesite visits, we would wait until the next morning to visit our first cemetery. Not wanting to waste the evening, though, we had a few errands to run. Our first stop after we checked in to the Hampton Inn Kerrville and stashed our bags was at the County Courthouse. On the west side of the courthouse stands the Kerr County War Memorial. Composed of five connected columns, alternating between black granite and white limestone, it bears the names of 88 men from Kerr County who died while serving their country. 19 from World War I, 48 from World War II, six from the Korean War, 12 from the Vietnam War, one from Operation Enduring Freedom and two from Operation Iraqi Freedom. In the Vietnam War section, listed fifth from the top is Duane A Johnson, the reason for our visit to Kerrville.

After spending a few minutes at the Memorial, we moved on, soaking in the evening sun and enjoying the heat at a local park, before making a quick trip to Walmart to stock up on essentials. We wrapped up the day by testing out the hotel pool and hot tub, before settling in for the night.

At 8:00 AM on the morning of October 6th, 2020, we met with a man named Melvin Jones at the Cracker Barrel restaurant just a few hundred yards from our hotel. Melvin had responded to a Facebook post that I had posted on the “Kerrville TX Message Board” Facebook Group. He and I had shared a few messages, and then a short phone call in the weeks prior to my trip. He didn’t know Duane very well, but they had graduated from Tivy High School together in 1965. When he called me, he thanked me for what I was doing and offered to meet us for breakfast and then head to the cemetery and lead me to Duane’s headstone.

Melvin had served his country as well, although not until after he graduated from college in 1969 and was commissioned a Second Lieutenant. He was shipped to Korea, which was no cakewalk. The ongoing racial strife coupled with a unit filled with disenfranchised career soldiers and recent returnees from combat made being a junior officer in Korea almost as dangerous as being one in Vietnam. As the Vietnam War ended, a massive reduction in force was needed, and he gladly resigned his commission in order to enter back into civilian life.

After we finished eating, we set out for the Garden of Memories, located just northeast of Kerrville. The cemetery straddles Texas Route 16 and is extremely well kept. We followed Melvin’s truck as he turned right into the east side of the cemetery, away from the cemetery office. Another quick right puts us on a cemetery road that splits this eastern section into two parts. We parked and exited our vehicles. Melvin had asked me on our phone call weeks ago if there was anything I needed. I wanted to place a small American flag at each headstone, and so I asked if he could find around a dozen small flags for me. He happily obliged and presented me with a dozen 6”x 8” flags on wooden stakes, along with another dozen smaller 3”x 5” flags on plastic stakes. Just as with our breakfast at the Cracker Barrel an hour earlier, he would not accept my offer to repay him. These were my first tastes of Texas hospitality, and they would not be my last.

Melvin led us a few feet into the cemetery, where, just under the outstretched branches of a large twisted oak tree, lies the final resting spot of SGT Duane Aaron Johnson, Alpha Company, 3rd Battalion, 12th Infantry Regiment. As far as I know, Duane is the only member of his family buried in Kerrville. His brother Dennis, who also served in Vietnam, lives in Dallas now. Dennis and I have emailed occasionally, and he is appreciative of my efforts in telling the story of the 3-12 Infantry. He couldn’t come down to Kerrville and meet me but sent me several pictures of his brother in Vietnam.

This section of the cemetery consists of nine rows that parallel Texas Route 16. Duane’s headstone is in the third row, and a constant flow of traffic in and out of Kerrville disrupts what could be a very peaceful setting. Further adding to the din, during my visit, a nearby work crew was using a jackhammer to remove an old headstone in preparation for the installment of a new one. I ignored the noise and focused on the physical area around me. Large live oak trees are spread throughout the cemetery, perhaps one every 200’ or so. From Duane’s grave looking southeast, a sparse wall of trees stands at the edge of the cemetery, partially hiding the gently downward sloping hillside that ends in Rattlesnake Creek, which flows south through town and empties into the Guadalupe River.

Duane Aaron Johnson was born on October 25, 1947. His family lived in Edinburg, Texas for many years, where he and his brother played both Little and Pony League baseball and spent every chance they got hunting and fishing. Eventually his family moved to Kerrville either just before or during his senior year of high school. He graduated high school in 1965, and while other graduating seniors from Tivy high school have extracurricular activities listed under their senior picture, the caption under Duane’s simply says “Transfer Student.” Duane’s father operated the local bakery. In one of his letters home, Duane mentioned his pack being heavier than the sacks of flour he and his younger brother Dennis often carried for their father at the bakery. In 1967, Duane received his draft notice, and in August of that year reported to the Kerr County Courthouse to be inducted into the United States Army. After he completed basic and advanced infantry training at Ft. Polk, Louisiana, he was sent to Vietnam, arriving on January 12, 1968, just two days after Garnett’s uncle Donald. Without knowing for sure, there’s a chance that the two men in-processed Vietnam together at Cam Ranh Bay and flew to Pleiku in the Central Highlands together just a few days later.

Duane was assigned to Alpha Company and was placed in the 3rd platoon under the command of 1LT Bill Kurtines. In his memo book, the young platoon leader notes then PFC Johnson’s name, service number, DEROS date, ETS date, R&R month and location, date of birth, date of rank and weapon serial number. This memo book, used by 1LT Kurtines throughout his tour, was adjusted as his tour progressed. In small blue letters, written above Duane’s original rank of PFC, Kurtines added SP/4, denoting the rank of Specialist Fourth Class. And finally, written perpendicular to the rest and in all capital letters, he wrote KIA 14 AUG 68. The one-day discrepancy between Duane’s actual KIA date and the one noted in the memo book can most likely be attributed to the fact that 1LT Kurtines was not with the company on August 13th and 14th, but was on his duly earned R&R. When he arrived back to the company in the days following, imagine his shock in learning that over half his platoon had been killed or wounded on those two fateful days in August. While getting an update on his men’s condition, Duane’s death on the 13th was inadvertently lumped into the 14 KIA and over 20 WIA suffered by Alpha Company on the 14th.

August 12th, 1968 – Kontum Province, Republic of South Vietnam

Duane and the rest of 3rd platoon, along with Alpha Company’s 1st Platoon, had been airlifted by Huey helicopter to Fire Support Base(FSB) 29. The unit was given the mission of moving roughly seven kilometers southwest of FSB 29 to join the Recon Platoon element that had been observing heavy NVA movement near their location for several days. Alpha was to be dispersed into several elements, acting as a recon screen for the FSB, and hopefully preventing a full-scale attack bent on overrunning the American position.

While 1st platoon was able to make their planned night locations, 3rd platoon failed to reach their target, and established a hasty night defensive perimeter. SFC Henryk Sulatyki, a native of Poland who had been forced into a labor camp by Nazi Germany in the 40’s and then subsequently enlisted in the US Army upon his liberation in 1945, led the platoon while 1LT Kurtines was on R&R.

August 13th, 1968

3rd platoon, consisting of approximately 30 men, moved out at first light. Duane Johnson’s squad led the patrol. With over 200 days in Vietnam, he was considered one of the most experienced squad leaders in the platoon. Also accompanying the platoon was a specially trained dog handler and his tracker dog. Although he could have had one of his men take the lead, or point position, Duane volunteered to lead from the front. Behind him, in the slack position, was SP4 Linwood Jones, an experienced man with nearly four months in country.

At approximately 0830, roughly 300 meters into their movement, the lead squad was hit by a long burst from an NVA machine gun. Duane Johnson took the full brunt of the burst and was killed instantly. Linwood Jones in the slack position was wounded severely. The platoon returned fire, and silenced the machine gun, killing a single NVA soldier. SFC Sulatyki’s men recovered Duane’s body, while SP4 Bobby Santoro, the platoon medic, treated Jones’s wounds and prepared him to be moved. The platoon struggled as they moved the two men back towards their previous night location near Hill 826, some 700 meters to the northeast.

4th Platoon, which was marching overland from FSB 15 to the east, was immediately ordered to be airlifted to the site of the contact, however bad weather prevented the airlift. Instead, they moved overland to link up with the 3rd Platoon at Hill 826. There, 3rd Platoon had joined up with a patrol from Delta Company that had established a Landing Zone. The two Alpha Company platoons combined and moved out towards the recon position as originally intended. The Delta Company patrol waited for a medevac helicopter to arrive, and the wounded SP4 Jones and the body of Duane Johnson were finally evacuated.

Specialist Fourth Class Duane Johnson would be awarded the Bronze Star and Purple Heart and be posthumously promoted to Sergeant. His body was evacuated to the rear, where it was processed by US Army mortuary affairs specialists and shipped back to the United States to be claimed by his family.

For 3rd platoon, the loss of Duane Johnson and Linwood Jones was just the beginning. After linking up with the 4th Platoon, the combined unit moved back to the southwest towards the small streambed separating them from the recon position on a hilltop rising around 100 meters from that narrow valley. Running out of daylight, they established a night defensive perimeter intending to complete their movement early the next morning.

At first light, the two platoons moved across the streambed and up to the Recon position. The units combined, and at 1530, Recon was airlifted out. 1LT Leo Hadley and his command group of Radio Telephone Operators and a Forward Observer from 6-29 Artillery caught a ride to the 3rd & 4th platoon position on the Hueys. Although still a junior 1LT, Leo had been hand selected to be the company commander of Alpha Company by LTC Jamie Hendrix, the battalion commander of the 3/12 Infantry.

As the men began to expand their foxholes and prepare for their first night in the NDP, the North Vietnamese launched a vicious rocket and mortar attack on their position. Lacking overhead cover, the airbursts sent shards of metal and wood down into the open topped foxholes below. 15 men would be killed, including 1LT Hadley, and another 20 or so wounded. The survivors withdrew to the streambed at the foot of the hill. It was Alpha Company’s worst day in Vietnam.

Mr. & Mrs. Willard Johnson of Kerrville, Texas applied for a military grave marker on August 31, 1968. Hillsboro Monument Works was awarded the contract to supply a flat granite marker with a Latin cross emblem displayed on it. Also included were the following words.

DUANE A JOHNSON

TEXAS

SGT US ARMY VIETNAM

BSM – PH

OCT 25 1947, AUG 13 1968

After placing a small American flag and a penny on the headstone of SGT Duane Aaron Johnson, we left the Garden of Memories, completing our time in Kerrville. Next up, a 100-mile drive to the southeast to the Cementerio Catolico San Jose in Jourdanton, Texas, and the final resting place of PFC Antonio “Tony” Garza.

Post Script

It has been over two years since Micah and I visited Kerrville and the gravesite of Duane Johnson. So much has happened since then. My family moved from our home state of Alaska to West Virginia. Our second oldest child graduated from high school and is off on her own, commercial fishing during the summer and finding multiple adventures to keep her busy during the winters. My communication with Dennis Johnson has continued. Not long after I returned from Texas, he sent me all of Duane’s tour photos and letters home. I was able to scan both photos and letters, and return the originals along with a digital copy, ensuring those precious family treasures would never be lost.

Through my continued research, I’ve also made contact with family members of others lost on August 14th, 1968, including 1LT Leo Hadley’s sister Linda, who has become a dear family friend. With each new contact I make, I’m able to shed a little bit more light on the untold stories of the men of the 3rd Battalion, 12th Infantry Regiment.