September 9th, 2024

On the road once for work, I found myself in early September of 2024 in Milford, Pennsylvania, located just miles away from the tri-state border of Pennsylvania, New Jersey and New York. The rest of my work group would be flying in, but I had driven from my home in West Virginia and given myself some extra time in order to make a gravesite visit before everyone arrived.

Most of the gravesites that I have on my list are of men that were serving in the 3rd Battalion, 12th Infantry Regiment in Vietnam when they lost their lives. In my research of the battalion though, I realized that there were dozens of men from other units who died either while attached to the battalion, (but not assigned), or while assisting the battalion through their mission as an artilleryman, aviator or engineer. I began adding their names to the casualty list I’d compiled and the map I’d created, which showed the final resting places of over 265 men connected to the 3-12 Infantry. If I got the chance, I’d try to visit their gravesites. The final moments of their lives were spent alongside or supporting men from the 3-12, and I wanted to learn their stories.

The gravesite I planned on visiting was located in Montgomery, New York, 35 miles east of Milford. I left my hotel around 8:30 in the morning, and headed east on Interstate 84. During the short drive, I had time to reflect on what I knew about the soldier whose grave I was about to visit.

Warrant Officer Thomas Edward Adams – January 31st, 1967

Thomas Edward Adams was the son of Harold and Veronica Adams. Before joining the Army, Thomas had lived with his parents and two siblings in the village of Maybrook, New York. He was trained as a helicopter pilot and arrived in Vietnam on June 8th, 1967. He was assigned to the 498th Medical Company, (Air Ambulance), a part of the 55th Medical Group, 44th Medical Brigade. Based in Qhi Nhon on the central coast of Vietnam, the 55th sent its UH-1H Huey medevac helicopters out to numerous forward airfields in the Central Highlands.

On December 31st, 1967, Warrant Officer Adams and three other men from the 498th Medical Company were alerted for a mission north of the 4th ID basecamp at Dak To. A man from Bravo Company, 3-12 Infantry had been running a high fever for hours, and the situation was critical. The weather was not cooperative. High winds, rain and a low cloud ceiling made the mission nearly impossible but medevac pilots and crews were trained to deal with the weather, and could have turned down the mission if they felt it was too dangerous. WO William Cheney, the senior pilot on this mission with over 10 months in Vietnam, made the call. They would go and attempt to pull this severely ill soldier out of a small landing zone near an old abandoned French fort. The other men on board the aircraft were PFC William Holland, the crew chief, and a medic named Specialist Fifth Class Lopez.

As Cheney and Adams piloted the UH-1H Huey toward the landing zone, the weather worsened. The thick clouds hid the setting sun, the low light increasing the danger. At approximately 1900 hours, the men from Bravo Company heard the Huey pass overhead. Seconds later, the familiar and comforting sound of Huey rotor blades beating against the sky was replaced by the horrible sound of crunching metal and splintering tree branches. The Huey, which had begun a left turn after passing over the LZ, had slammed into a hilltop just west of the French Fort.

An element of Bravo Company was sent out in the direction of the crash, but was halted by the worsening weather and thick inky blackness of night in the jungles of Vietnam. At first light, the men resumed the search, and soon found the smoldering wreckage of the Huey. The bodies of pilots William Cheney and Thomas Adams and crew chief William Holland were quickly located. They had all been killed in the impact and ensuing fire. As the men from Bravo searched the area for the missing medic, they heard a faint cry.

“Help me…”

Miraculously, SP5 Lopez had survived the crash. He was badly burned, but the Bravo men were able to stabilize him and called in another medevac, which successfully evacuated Lopez for more advanced care in the rear.

Back in the Bravo Company landing zone, another miracle occurred. The man with the 106 degree fever, so close to death himself, began to recover. At some point during the long night, his fever had broken.

The chaos of war cannot be defined. Survivors of incidents like this ask themselves “why me?”. How and why does one man survive when three don’t? Why does a life threatening fever break only after three men die attempting a rescue? There isn’t any logical answer. It’s the chaos of war at work.

Montgomery, New York

The drive from Milford to Montgomery was pleasant. Just a few minutes after exiting I84, I pulled into St. Mary’s Cemetery. A small cemetery office stood next to the parking area, and the front door was open. I walked in, and was immediately greeted by a woman named Sue Heck, who was sitting at a desk in the small room. When I introduced myself and asked if she could help me find the gravesite of Thomas Adams, she quickly agreed. No need to look in the records, she said she knew exactly where his gravesite was, and we began walking into the cemetery.

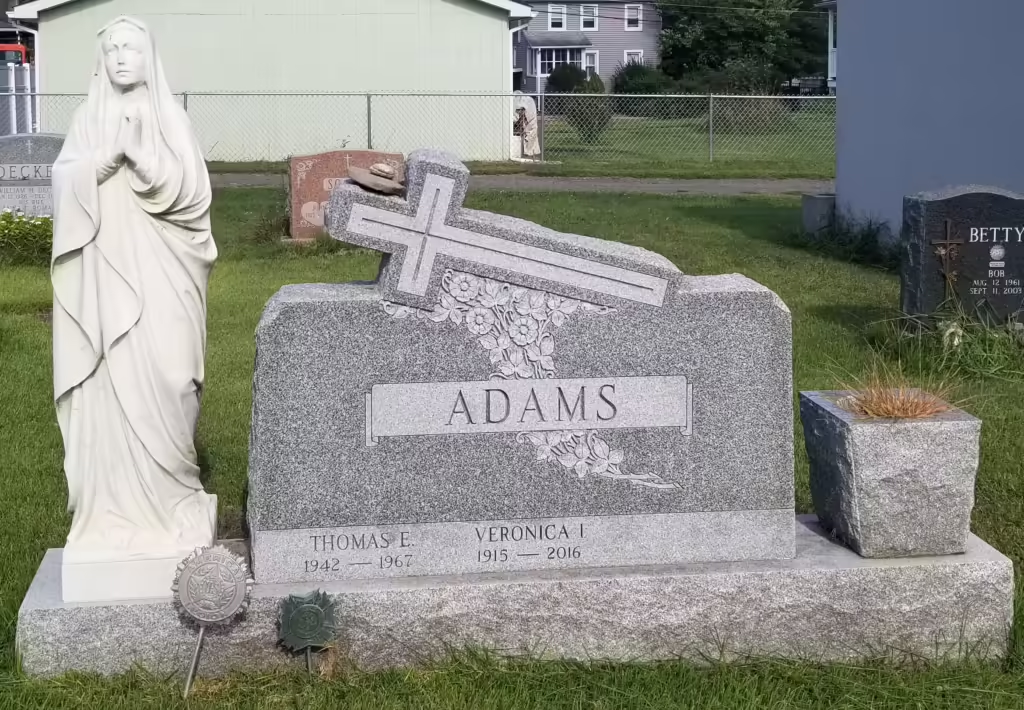

Just a short walk from the office stood a tall upright headstone adorned with the name Adams. Bracketed by a large statue of the Virgin Mary on one side and a stone planter on the other, the large headstone bore two names. Thomas E (1942-1967) and Veronica I (1915-2016). Thomas’s flat military marker was placed at the foot of his grave, which is customary when a larger stone occupies the head.

Sue and I chatted for a few minutes. She filled me in on what she knew of the family. Her grandmother and Thomas’s mother Veronica had been friends, and Sue had heard about Thomas’s loss in Vietnam her whole life. She mentioned that there was a sister who lived in upstate New York, but there was no longer any family that lived locally. We finished our conversation and Sue headed back to the office, leaving me to accomplish my little mission.

I walked back to my truck to retrieve a small American flag, my pruning shears, and small straw broom. The cemetery and gravesites were well kept, but there were a few long strands of grass along Thomas’s flat marker and at the base of the large upright stone. I cleaned the area up a bit, placed my flag and penny and took a few photos. The cemetery that morning was so peaceful. The early autumn air was cool and crisp, and I couldn’t really feel the heat of the morning sun.

Sue had mentioned that Thomas and his family lived in nearby Maybrook, which was about two miles south of Montgomery. I had the address of his family home, and she encouraged me to drive over and check out the town, now just a shell of the booming railroad town it was in the ‘60s. Before leaving, I placed another penny under the crook of a large stone crucifix atop the upright headstone. The penny on the flat marker would likely get knocked off the next time the mower went through, but maybe this one, partially protected from the elements, would stand the test of time.

From St Mary’s Cemetery I left Montgomery, drove south across Beaver Dam Road for a couple of miles and entered the village of Maybrook. The casualty records listed Thomas’s home of record as 288 Highland Avenue. Within seconds of entering the village on Maybrook Road, I arrived at what should have been 288 Highland. The house numbers jump from 210 to 302, and a medium sized city lot stands vacant where 288 most likely used to be. I’m sure with a bit of sleuthing, I could figure out what happened to the home that once stood on that lot, but instead I’ll leave that little mystery alone.

I drove down a small hill into Maybrook proper. The old downtown area had seen better days. A few churches and old buildings surround a modern looking firehall, obviously an important part of the current town. Just a few blocks away stands a one story brick building. The local Veterans of Foreign Wars building. Still in use, with fairly fresh looking murals painted on two sides. I left my business card on the front door, with a small note about my quest for information about Thomas Adams. Maybe a VFW member would want to connect.

I left the little village of Maybrook and got back on Interstate 84. This time headed west and back to Milford, Pennsylvania. It was time to get ready for work.