February 2nd, 1969

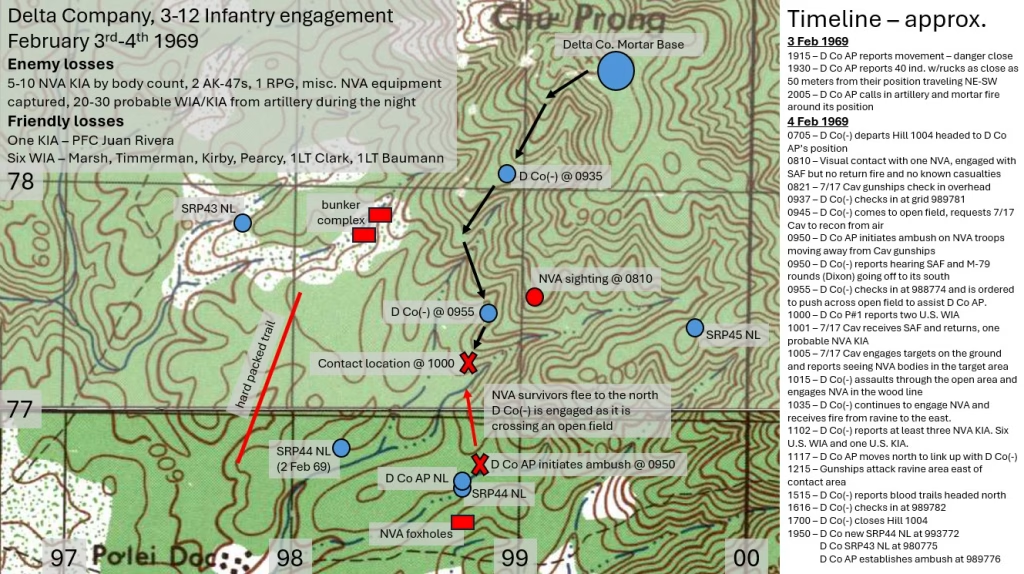

On February 2nd, 1969, Sergeant Jim Hagy, a tall muscular Rockville, Maryland native with over eight months experience in Vietnam, gathered three men the 1st Platoon of Delta Company, 3rd Battalion, 12th Infantry Regiment, 4th Infantry Division. He briefed them on their mission, checked their gear and weapons, and at 1630 hours, the small group of men stepped outside the perimeter of the Delta Company patrol base on Hill 1004 in the mountains west of Kontum City. The four-man element was given the callsign SRP44, which stood for Short Range Patrol 44.

Jim Hagy was a graduate of the U.S. Army’s Non-Commissioned Officer’s Candidate School. A “shake-n-bake” sergeant, he had earned his stripes before ever setting foot in Vietnam. He had graduated from the course at Ft. Benning, Georgia in February of 1968, then spent a couple of months training new recruits at Ft. Jackson, South Carolina before shipping out for Vietnam in May of that year. For some soldiers in Vietnam, the “instant NCO” status was a hard sell, and the shake-n-bakes were looked at with disdain by some of the experienced junior enlisted soldiers thrust under their supervision. But Hagy was a solid NCO, who looked and acted like he had been doing this all his life. His men trusted him, and eight months in Vietnam had given him an edge that was unmistakable. He had been through some tough days of combat since joining Delta Company in late May of 1968. Little did he know that some of his toughest days were still ahead.

SRP44 was a part of a five-element reconnaissance screen established by the Delta Company Commander, Captain Ronald Foss. Captain Foss, a 24-year-old graduate of the North Georgia Military College (Class of 1965), had assumed command of Delta Company in September 1968. Delta Company’s screen was part of a larger screen made up from elements of the battalion’s three other line companies, Alpha and Bravo to the north, and Charlie to Delta’s south.

SGT Hagy moved his small element to the southwest down a thousand-meter ridgeline, which emptied into a large valley filled with thickly foliaged hills. Interspersed with small creeks and rivers, or “blue-lines” as the men called them, due to their appearance on the military maps they used, this valley and the mountains around it was the home to several large elements of the North Vietnamese Army. The 66th NVA Regiment, a near constant opponent of the 12th Infantry Regiment, owned this part of the jungle, using a large network of tunnels, bunker systems and camps to move men and material hidden from the watchful eye of American surveillance assets. The SRP screen established by the 3-12 Infantry had a singular purpose. Find the NVA units and supply lines and call in the might of American air power and artillery to destroy them.

The four-man short range patrol (SRP) moved as silently as possible through the thick jungle, maintaining radio contact with company headquarters through a PRC-25 tactical FM radio. In such a small element, each man had a very specific role. The point man, armed with an M-16 rifle, led the way. His eyes, ears and nose focused on the jungle in front of him. Senses fully alert at all times, the point man position was given to someone who could be trusted. Just behind the point man was Sergeant Jim Hagy, the squad leader. From this position, he could keep one eye on the point man and occasionally check their position with his map and compass. He was responsible for keeping them on course and picking out their eventual night defensive position. Behind the squad leader was the radioman, carrying the 25-pound radio in addition to his M-16 and other gear. Last came the rear guard, who usually carried an M-16, but could also be armed with an M-79 40mm grenade launcher. Lightly armed, his job was to watch from the shadows and only fight if they were discovered.

On this patrol, the rear guard was Specialist Fourth Class Tom Dixon, from Wright City, Missouri. Dixon had been in Vietnam since mid-May of 1968. His over eight months of experience, and the M-79 grenade launcher he carried, were welcome additions to the patrol.

As darkness was falling on the night of the 2nd, the four men of SPR44 took up a position roughly two kilometers southwest and 350 meters below the company patrol base on Hill 1004. The jungle in Vietnam at night could be an unnerving place. Night noises from birds and animals had to be differentiated from the possibility of other noises that could be coming from NVA soldiers. For the men of SRP44, the night of the 2nd passed uneventfully.

February 3rd, 1969

As first light broke over the jungle west of Hill 1004, SGT Hagy’s team was on full alert. There had been no sounds of enemy movement during the night, but now that the light of day was pushing away the darkness, there was a real chance that the SRP might catch a glimpse of something. For several hours, the men lay in stillness. At around 1000 hours, SGT Hagy was satisfied that they were alone in the jungle, and the men took some time to prepare themselves for today’s movement to a new night location. C-ration cans and pouches were opened, and the contents consumed eagerly. By 1130, the men were ready.

SGT Hagy received orders to move his SRP to a new night position several hundred meters to the southeast. Once again, the men moved out. Point man, squad leader, radio man, rear guard.

Right around the same time SRP44 was moving out, another Delta Company 1st Platoon element began moving as well. Designated Ambush Patrol #1, this element was a little larger, and much more heavily armed. The seven-man team consisted of a squad leader, two machine gunners, at least one grenadier, and several riflemen. Unlike an SRP, an ambush patrol, as its name implies, had the mission to establish an ambush along a likely NVA travel route and engage the enemy.

At around 1240 hours, as the ambush patrol was moving in the same general direction as SRP44, they drew a short burst of NVA small arms fire from the south. The men hit the ground but could see no enemy targets. From high atop Hill 1004, Captain Foss directed the company’s 81mm mortar squad to fire several high explosive rounds into the jungle just beyond the ambush patrol’s position.

Captain Foss ordered SGT Hagy and SRP44 to hold their position. With NVA in the vicinity, and friendly mortar fire being directed, he needed to maintain precise situational awareness of his two elements as they worked in relatively close proximity to each other. Satisfied that he had control of the situation, he ordered SRP44 to continue to their planned night position. They would hold there and wait for AP#1 to link up with them before dark. The NVA were out there, and if they stumbled into one of his elements, having them together would allow them to hold their own until further support arrived.

Ambush Patrol #1, under the command of SGT Shepherd, was ordered to check out the mortar impact area and look for signs of the enemy. At 1445 hours, they called Captain Foss on the radio and reported that they had found a small bunker complex and indications of a fire that was used the night before or that morning. The “bunkers”, which were just small fighting positions, roughly three feet wide by four feet long, were dug into the earth approximately four feet. A trail running to the southeast was found nearby. No blood trails, enemy casualties or equipment were found. SGT Shepherd’s patrol completed its inspection of the area and began moving east toward SRP44.

Around 1800 hours, the two elements linked up. SGT Hagy was placed in command of the now 11-man element. He spent a few minutes getting briefed by the men in the ambush patrol about their contact earlier in the day. He was amused when the biggest complaint about the encounter came from one man, who had been on the receiving end of a 7.62mm round from an enemy AK-47. The round had torn through the man’s rucksack, ruining his favorite c-ration meal of pound cakes and peaches.

Hagy integrated the new men into his small perimeter and spaced them a few feet apart, mostly facing a rough trail to their north. Although 11 men was better than four, he couldn’t spread the men too thin. He placed the two machine guns toward either end of his small element, made sure he had a few men watching their flanks and rear and began to get settled in for the night.

Just around sunset, at 1845 hours, SGT Hagy spotted two NVA soldiers moving down the trail. Armed with AK-47s and wearing ruck sacks, the men came as close as 50 meters from SGT Hagy’s element. Two more men quickly followed at roughly 15-meter intervals. The NVA were traveling from the northeast to the southwest, likely heading toward the small bunker complex the ambush patrol had discovered earlier that day. Hagy whispered his report up to Captain Foss but then went silent. Another NVA soldier came sauntering down the trail. Hagy knew this wasn’t just some small patrol. This was a large element, far bigger than his 11 men. He continued watching the trail…. another soldier, and then another. All spaced evenly. The gaps between the men made it impossible for SGT Hagy to initiate his ambush. He now had close to ten enemy soldiers on one flank, and an unknown number still coming up the trail. There was no way to know just how large this NVA element was. So instead of firing on them, he counted them. After 39 had passed, he got off another quick radio call to CPT Foss.

Captain Foss began coordinating support from artillery units nearby. At around1930, with his men now fully hidden in the darkness of the night, SGT Hagy began calling in mortar fire from Hill 1004. 81mm and 4.2” mortar tubes erupted in the night, lobbing high explosive shells high into the sky and down into the area surrounding Hagy’s men. It was fully dark, and SGT Hagy was unable to accurately count the NVA moving around their area. He ended his count at 62 soldiers, but there were certainly more than that out there. What had started as four individual soldiers had turned into an estimated 100 soldier enemy infantry company.

Within minutes of the first mortar rounds bursting around Hagy’s perimeter, their larger cousin, the 105mm howitzer, entered the scene. Fired from the battalion firebase at FSB Roundbottom (Hill 1151), some 10 kilometers to the north, and at least two other firebases in the area, the high explosive shells began raining down amongst the NVA soldiers. SGT Hagy had no idea how deadly the artillery and mortar fire was, and it didn’t matter. The purpose was to create a curtain of American fire between his men and the roughly 100 NVA soldiers nearby. Well into the night and early the next morning, the mortarmen of the 3-12 Infantry and the artillerymen, or “redlegs”, of Bravo Battery, 6-29 Artillery manned their tubes, launching round after round into the dark night. The shrapnel from the exploding shells tore through the jungle, sometimes ripping through the air just inches over the heads of Hagy’s men. They hugged the ground, thankful for the powerful indirect fire support, but very aware that just one misfire or miscalculation could drop a friendly round on top of them.

For over four hours, Hagy’s men could hear men crashing through the jungle around them. The NVA were frantic, knowing there was an American unit close enough to call in artillery, but unable to find them amongst the darkness and exploding incoming fire. At times, individual NVA soldiers ran within a few feet of the hidden Americans.

Eventually, SGT Hagy called off the fire support. The tubes on top of Hills 1151 and 1004 fell silent. A stillness embraced the night, and soon the normal night sounds of the Vietnam jungle returned. SGT Hagy set a 50% alert, and for a few fleeting hours before daylight, the men attempted to rest.

February 4th, 1969

At first light up on Hill 1004, Delta Company commander Captain Ronald Foss formed a reaction force composed of his company command group, the artillery forward observer party, and around a dozen men from his 1st Platoon. He would lead the approximately 20 men down from the company patrol base toward the AP/SRP location to link up and perform a bomb damage assessment (BDA) on the impact area from the artillery and mortar barrage the night prior. The men set off from the patrol base just after 0700 hours.

As the reaction force reached the bottom of Hill 1004, they were joined by another American asset, this one from the sky. A Light Observation Helicopter, nickname “Loach” from Alpha Troop, 7th Squadron, 17th Cavalry flew overhead. The two-man scout helicopter buzzed the area between Captain Foss’s reaction force and Sergeant Hagy’s element, looking for signs of the enemy.

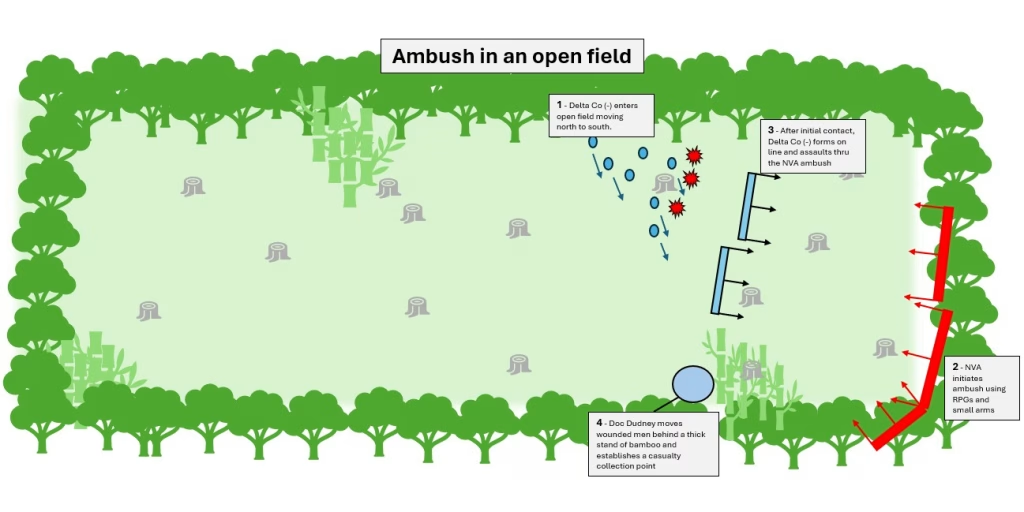

At 0945, Captain Foss’s reaction force reached the northern edge of a large clearing, shaped like a rectangle running west to east. This clear spot in the jungle had been caused by an explosion of American ordinance, but it had been some time since that explosion. Jagged stumps were all that were left of once mighty trees. The fire blackened stumps and a smattering of broken limbs dotted the now clear space. A few small stands of bamboo shot up from the reddish gray soil near the far edge of the clearing.

Captain Foss paused his patrol and requested that the Loach take a look. He wanted to close the distance between himself and Sergeant Hagy, but crossing an open area was never a good idea.

Unbeknownst to the Loach crew or Captain Foss, the helicopter buzzing around was about to become the impetus for a prolonged engagement.

Sergeant Hagy’s men were still hunkered down in their night defensive position. Torn and shredded leaves and branches littered the area, but the men were unscathed. Suddenly, a single NVA soldier moved into view and crouched behind a large tree, exposing his back to Hagy’s men. The NVA soldier looked up, obviously reacting to the Loach making passes a few hundred meters to the north.

With a quick nod to PFC Thomas Doughty, an M-60 machine gunner from the Catskills region of New York State, SGT Hagy initiated the ambush. Doughty squeezed the trigger, and a dozen rounds ripped into the unsuspecting NVA soldier, killing him instantly.

The jungle around Hagy’s position erupted. The night of artillery and mortar fire may have inflicted numerous casualties amongst the NVA, but some had come through the night in one piece. Down the ambush line, additional targets presented themselves and were fired upon. The NVA, obviously disoriented from the long night of artillery and mortar fire, couldn’t pinpoint Hagy’s exact position. Like many firefights in Vietnam, the two sides engaged each other from a distance, aiming at suspected locations and muzzle flashes rather than distinct targets. At least one NVA soldier crept close enough to throw a grenade. The small high explosive device, called a potato masher due to its distinct shape, landed just a foot or two in front and a little below the muzzle of Doughty’s machine gun. Sergeant Hagy, crouched to Doughty’s side, threw his hand over the M-60 just as the grenade went off. The gun leapt off the ground, smacking into Hagy’s outstretched hand. He pushed the weapon back to the ground with all his strength, and Doughty continued firing. The violence of the movement of the gun was severe enough that it ripped the nail off Doughty’s thumb, but other than that, the two men were unscathed.

Neither Hagy nor Doughty could see the soldier who had thrown the grenade but noticed a clump of bushes 20 or 30 feet away that kept moving unnaturally. Doughty squeezed off a few bursts toward the bushes. Hagy noticed that they were all going high. Hagy reached over and lifted up the stock of the M-60, causing the barrel to dip a little lower.

He remembered later, “The bushes quit wiggling. We found that guy laying there when it was all over with.”

A few meters away from Hagy and Doughty, SP4 Dixon was pumping round after round of 40mm grenades into the jungle around his position. He wasn’t a huge fan of the weapon, as the rounds could be deflected or even bounced backwards if they struck a branch or tree before they traveled the 15-20 meter distance required before arming. Suddenly, after firing seven or eight rounds, the weapon jammed. Dixon opened the breech, but the spent casing was stuck fast. He cursed the weapon and urgently tried to pry the shell out. After a few minutes he gave up, threw the useless weapon to the ground and grabbed the M-16 of Private First Class Charles Pearcy, who had been wounded in the arm by shrapnel.

Before the firefight was over, Sergeant Hagy would have another close call with a grenade, this time an American one. Throwing grenades in a jungle was risky business, as the triple canopy forest was filled with thorny bushes, overhanging branches and all manner of obstacles for a thrown object. Beside Hagy, another soldier rose to his knees and hurled a grenade out toward the enemy. It immediately struck a branch and plopped down on top of the small mound Hagy was sheltering behind. In what seemed like slow motion, the grenade teetered at the top, then rolled down the opposite side before exploding harmlessly.

On the other end of the ambush line, PFC Julio Cotto-Melendez, armed with an M-60 machine gun, kept a nearly constant barrage of 7.62 rounds pouring into the enemy positions. Cotto was known for the set of airborne wings he wore on his fatigue shirt. The 4th Infantry Division was not an airborne unit, so very few men in the Division had completed the airborne school at Ft. Benning, Georgia. When asked how many times he had jumped out of an airplane, Cotto replied, “None. I was pushed out 11 times.”

Less than six hundred meters to the north, Captain Foss and his men heard the sudden cacophony of machine gun, M-16 and AK-47 fire erupt. Mixed in with the noise was the familiar bloop of the M-79 grenade launcher.

Captain Foss, who had been contemplating an alternate route around the open area in front of him, was forced into a decision. His men needed support, and they needed it now. He ordered his men to move across the field as quickly and tactically as possible.

Just seconds after SGT Hagy’s element initiated their ambush, Captain Foss’s element walked into one of their own.

On the eastern side of the field, a small group of NVA soldiers had joined together into a rough ambush position. Armed with rocket propelled grenades, AK-47s and at least one machine gun, they could ignore the firing behind them since they could now see a group of American soldiers beginning to enter the open field to their front.

They waited until the first Americans were in the middle of the field and then initiated the ambush. The first burst of fire sent the G.I.s sprawling to the ground.

Patrick Dudney, the 1st Platoon medic remembered that moment.

“I remember being on the ground as if I had been slammed to the earth. There was no thought process. One second, I’m walking cautiously across this burned-out piece of jungle and within a split second I was lying on the ground. I had no idea where the rifle fire was coming from, but I had an idea it was from the edge of the clearing.”

1LT John Clark, born in Indiana but a graduate of the University of Miami (Class of 1966), was the platoon leader of Delta Company’s 1st Platoon. He started yelling cease fire, possibly thinking that the firing was coming from Sergeant Hagy’s ambush patrol. Still on the ground, “Doc” Dudney saw the Loach fly over the tree line on the south side of the clearing. At the base of a large tree, an NVA soldier with a giant fern attached to his belt for camouflage stood up and scooted around the base of the tree. As the Loach would circle the tree, the NVA soldier would move to the other side, masking him from the helicopter crew’s view.

Doc Dudney yelled to Sergeant First Class Gene Goff, the 1st Platoon sergeant and asked if he should shoot the NVA soldier. SFC Goff told him to hold off, as he was worried the Loach might mistake Dudney’s fire for enemy fire. Instead, Goff called the Loach pilot on the radio and told him about the NVA soldier. The Loach circled back again, dropped a white phosphorous grenade at the base of the tree, and then worked the entire area with its mini-gun.

During a momentary lull in enemy fire, Captain Foss jumped to his feet. Like a surreal scene torn from an old war movie, he screamed at his men to rise and assault through the ambush. The enemy fire immediately intensified, but the Delta Company soldiers responded, getting to their feet and returning fire into the tree line.

The men moved into a line formation, and Dudney fell into place between PFC Juan Rivera, a 20-year old Puerto Rican soldier from New York City to his left, and 1LT Clark to his right. Richard “Preacher” Timmerman from Wisconsin was to 1LT Clark’s right. The men closed the distance to the tree line, firing their weapons as they did so. Not every medic in Vietnam carried a weapon, but Dudney did. He had named his M-16 “Moody Judy”, and now, for the first time since he arrived in Vietnam, she was firing shots in anger against the enemy. Dudney moved the selector switch to automatic and quickly burned through two or three 20-round magazines.

“Doc! Get behind me in case somebody gets hit!” yelled 1LT Clark above the din of small arms fire.

Dudney immediately switched his selector switch to semi-auto, and stutter stepped his way sideways and behind his platoon leader. Suddenly, the whole world went black.

When Doc regained his senses, he was lying on the ground, and Timmerman was beside him, yelling that 1LT Clark was hit. Somehow, Doc Dudney was unscathed.

An enemy rocket propelled grenade had slammed into the group of men, scoring almost a direct hit on PFC Rivera. Doc and Timmerman quickly grabbed the badly wounded 1LT Clark and dragged him toward a small depression behind one of the stands of thickly packed bamboo. Doc then ran to Rivera to see what could be done. It was too late; he had been killed instantly by the explosion.

“I thought at first, we had found the wrong person for his face was no one I recognized. Then the realization hit me that this was death at its worst.”

Nothing could be done for Rivera, but Doc had other wounded soldiers to worry about. He sprinted back to 1LT Clark and assessed the situation. Blood poured from severe shrapnel wounds on his arms and legs. Timmerman helped Dudney dress the wounds. While the two men were dressing the wounds, the NVA RPG gunner fired another round toward the group of men. It exploded, further wounding 1LT Clark.

Timmerman, who had also been wounded in the initial explosion, finally sat down and let Doc treat his wounds. Shrapnel had penetrated deep into his thigh and calf. Doc applied pressure dressings to both areas and assured “Preacher” that he’d be alright.

Across the American assault line, individual soldiers performed with undaunted courage and skill as they engaged the enemy.

PFC James Abe from Maryland was a member of the Captain Foss’s command element. At some point, he spotted an NVA officer among the trees and killed him, helping to further disrupt the already disorganized NVA element. Another member of the company CP group, PFC Donald Daugherty, continually exposed himself to enemy fire as he delivered a steady volume of rifle fire into the enemy positions in the tree line.

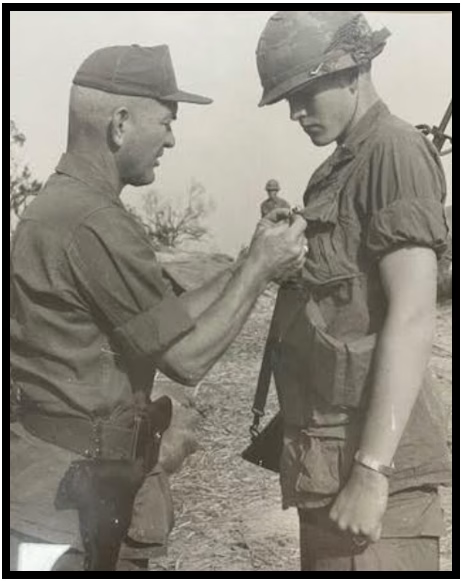

When 1LT Clark was wounded, SFC Goff immediately assumed the role of platoon leader for 1st Platoon. He turned to Staff Sergeant Fred Carson, a “shake ’n ’bake” NCO like SGT Hagy, and informed him that he was now the platoon sergeant. Even though SSG Carson was relatively new in country, he didn’t hesitate. He moved from soldier to soldier, encouraging each one to keep up a heavy volume of fire and defeat the NVA ambush. Carson would be awarded the Bronze Star Medal with Valor Device for his actions that day.

Another new soldier was PFC Dan Krisch. Hailing from Illinois, Krisch had only been in country for three weeks, and with Delta Company less than two. Trained as a mortarman, he had been assigned to 1st Platoon as an infantryman. On February 4th, he earned his Combat Infantry Badge and helped get his new unit out of a close NVA ambush.

SP4 Gerald Marsh, an experienced team leader with over six months in country was wounded in the initial engagement. He ignored his wounds and stayed on the line delivering fire until the enemy ambush had been defeated. As the enemy fire died down, Marsh limped over to Doc Dudney’s casualty collection point.

“Hey Doc, when you’ve got time, would you mind looking at my knee?” he asked calmly. A piece of shrapnel had punctured his skin just behind his kneecap. Doc dressed his wound, administered morphine, and then began filling out field medical cards for the wounded men.

The NVA RPG gunner fired another B-40 rocket toward Doc and the group of casualties. Miraculously, the round did not detonate. Instead, it came to rest wedged between the tightly packed stalks of bamboo, just over the heads of Dudney, Clark and Timmerman.

1LT Jerry Baumann from Marble Falls, Texas, an artillery forward observer (FO) assigned to Bravo Battery, 6th Battalion, 29th Artillery Regiment, but attached to Delta Company, spotted an NVA soldier who was armed with an RPG. 1LT Baumann and PFC Jesse Romo Jr (also from Texas), maneuvered into good positions and lobbed grenades at him. The grenades did the trick, silencing the gunner, but Baumann was wounded by shrapnel that peppered his backside, knocking him down. His radio operator, Corporal Michael Harper saw his lieutenant in an exposed position. He rushed forward, engaging targets as he went, and then pulled 1LT Baumann back to Dudney’s position.

Once there, Baumann was deeply embarrassed to tell Doc where his wounds were. Doc instructed him to pull his trousers down so he could get a look at the wounds. When 1LT Baumann attempted to refuse, Dudney threatened to cut his pants off. “You will not!” stated Baumann obstinately. Captain Foss intervened. “FO, let him see your ass.” That ended the discussion, and Doc used a large white bandage tied around his waist to cover both cheeks, which only added to his humiliation.

During another lull, PFC Steve “Smokey” Kirby walked up to Doc Dudney’s collection point. Blood streamed down his face. A jagged piece of shrapnel had slashed across Smokey’s face, leaving a deep gouge a few inches above the bridge of his nose.

Slowly, a calm descended on the battlefield. Any NVA that were left sandwiched between the Delta Company reaction force and the ambush patrol escaped to the flanks. A Cobra gunship showed up and began laying rockets and machine gun fire into a deep ravine to the east of the contact site.

As the medical evacuation helicopter arrived over the clearing, Doc and some of the other men threw their bodies over the wounded to shield them from the flying dust and branches kicked up by the Dustoff helicopter’s rotor wash. Soon after 1LT Clark, Timmerman, Marsh, 1LT Baumann, Kirby, and the body of PFC Rivera were evacuated, Doc received another request for aid. Several wounded NVA soldiers had been discovered. Doc was reluctant to treat these men who had so recently inflicted pain on some of his friends and tried to kill him. He pushed his reluctance aside and rendered aid until another Dustoff helicopter showed up to evacuate them.

The engagement over, Captain Foss ordered his men to continue in the direction of the ambush patrol, who had completed their own engagement with the enemy. SGT Hagy’s men had taken refuge behind a large, downed tree, and were glad to see the rest of their platoon and the company command group show up. The two groups merged and began another quick search of the battlefield. Several more wounded and dead NVA were found, along with valuable enemy maps, overlays and equipment.

The soldiers of Delta Company finished policing the battlefield and began the long movement back up to the company patrol base on Hill 1004. The battle-weary men from Delta Company entered the patrol base perimeter just as darkness was beginning to fall across the Central Highlands of Vietnam. The men scattered to their bunkers and foxholes. 1st Platoon was still responsible for a sector of the perimeter, and most men would spend a few hours that night on guard duty. For Patrick “Doc” Dudney, he welcomed guard duty and staying awake.

“I will never forget this day. It was getting dark as we arrived back to our perimeter. I remember having to pull guard down on the line that night. We had some vacant spots to fill. Pulling guard was OK with me. I knew we were all exhausted, but sleep didn’t come that night. Every time I closed my eyes, Juan awaited me.”

Author’s Note

In the days and years that followed, the men involved in the engagements on the 3rd and 4th of February 1969 tried to make sense of all that had happened that day. Some were recognized for their bravery. 1LT John Clark never returned to the unit. His wounds were too severe. He was medically retired from the military, and for many years battled the demons that tried to convince him that he hadn’t done enough. Captain Foss was relieved of command in late March when Delta Company was nearly overrun on a mountain top west of Hill 1004. Many of his men felt that he was the scapegoat for a greater failure of command which had left Delta Company understrength and vulnerable after weeks of intense combat.

For most of the men, it was a day to put behind them, at least until they too could set the uniform aside and live in peace. Some have very few memories of that day, while others, like Patrick Dudney, remember it vividly. There is no right or wrong way to remember one’s time in combat. Through many conversations, and historical documents, my hope is that this account gives a glimpse of what those days were like. Each man who survived them will have a different perspective, and any errors or omissions are not purposeful attacks against the lived memories of those valiant men.

A special thank you to Patrick Dudney, Tom Dixon and Jim Hagy, who so graciously allowed me to interview them about these events. This article was written in memory of PFC Juan Rivera.

Known Commendations

Private First Class Juan Rivera – Bronze Star with Valor Device (posthumous), Purple Heart (posthumous)

First Lieutenant Jerry Baumann – Silver Star, Purple Heart

First Lieutenant John Clark – Bronze Star with Valor Device, Purple Heart

Staff Sergeant Glenn Fred Carson – Bronze Star with Valor Device

Sergeant James Hagy – Silver Star

Corporal Michael Harper – Bronze Star with Valor Device

Specialist Fourth Class Gerald Marsh – Bronze Star with Valor Device, Purple Heart

Specialist Fourth Class Patrick Dudney – Bronze Star with Valor Device

Private First Class Marshall Steve Kirby – Purple Heart

Private First Class Richard Timmerman – Purple Heart

Private First Class Charles E Pearcy – Bronze Star with Valor Device, Purple Heart

Private First Class James Abe – Bronze Star with Valor Device

Private First Class Julio Cotto-Melendez – Bronze Star with Valor Device

Private First Class Donald Daugherty – Bronze Star with Valor Device

Private First Class Jesse Romo Jr – Army Commendation Medal with Valor Device

Bibliography

Interview with Patrick Dudney, December, 2025

Interview with Jim Hagy, December, 2025

Interview with Tom Dixon, December 2025

Daily Staff Journal, S-3 Operations, 3rd Battalion, 12th Infantry Regiment, February 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 1969 – retrieved from the National Archives

4th Infantry Division 1969 General Orders 410, 490, 601, 1656, 1667, 1937, 1945, 1949, 1953, 1955, 1958, 1962, 2268 and 2290 – retrieved from the National Archives

Casualty information for Juan Rivera – courtesy of the coffeltdatabase.org

Information for Marshall Steve Kirby – https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/283450490/marshall_steven-kirby

Information for Charles E Pearcy – https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/109141653/charles_e-pearcy

Information for Gerald L Marsh – https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/154585125/gerald-leon-marsh

Obituary for John Clark – retrieved from Ancestry.com

Obituary for Ronald Foss – retrieved from Ancestry.com